Technology Is Neither Hero Nor Villain: It's a power we decide to use for either good or evil

- Loren Taylor

- Dec 15, 2025

- 6 min read

In today’s reality, the use of tools like AI, blockchain, Automated License Plate Readers (ALPR), drones, self-driving cars, and other innovations is no longer simply an academic debate. These are levers that, if not used, will perpetuate an unsatisfactory status quo, and when applied, they can either deepen the harm or help us rebuild trust, safety, and connection. And we must make these choices in a moment of real strain.

Yes, Oakland’s safety crisis persists… even as we’ve made progress

In 2023, Oakland recorded roughly 15,500 violent crimes and more than 43,000 property crimes, giving the city one of the highest violent crime rates in the country at four times the national average. That reality shapes daily life for residents, workers, and small businesses.

While the trajectory has shifted, leading to overall crime reductions by 30-40% compared to 2023, including double-digit declines across multiple serious crime categories, it also needs context. Cities across the country are seeing similar downward trends, driven by a combination of post-pandemic normalization, focused enforcement, community-based violence prevention, and smarter use of data and technology. Oakland’s improvement reflects a national shift, not a single local fix. And Oakland crime rates remain unacceptably high - one of the highest in California.

That perspective should guide our next move.

If crime is falling nationally and locally, the question is not whether safety efforts work, but instead, it’s whether we are willing to strengthen what’s working and govern it responsibly. This is where technology like Flock’s automated license plate readers (ALPR) enters the conversation.

ALPR systems are not cure-alls. But they are proving to be force multipliers. They are helping clear violent crimes, identify suspects faster, and disrupt repeat offenders when used with clear rules and oversight. In a city still far more dangerous than it should be, refusing effective tools isn’t caution… It’s complacency.

Here’s the harder truth: progress is fragile. Crime declines can reverse as quickly as they arrive. Sustaining this momentum will require Oakland to pair continued investment in community safety with responsibly governed technology that supports, rather than replaces, human judgment.

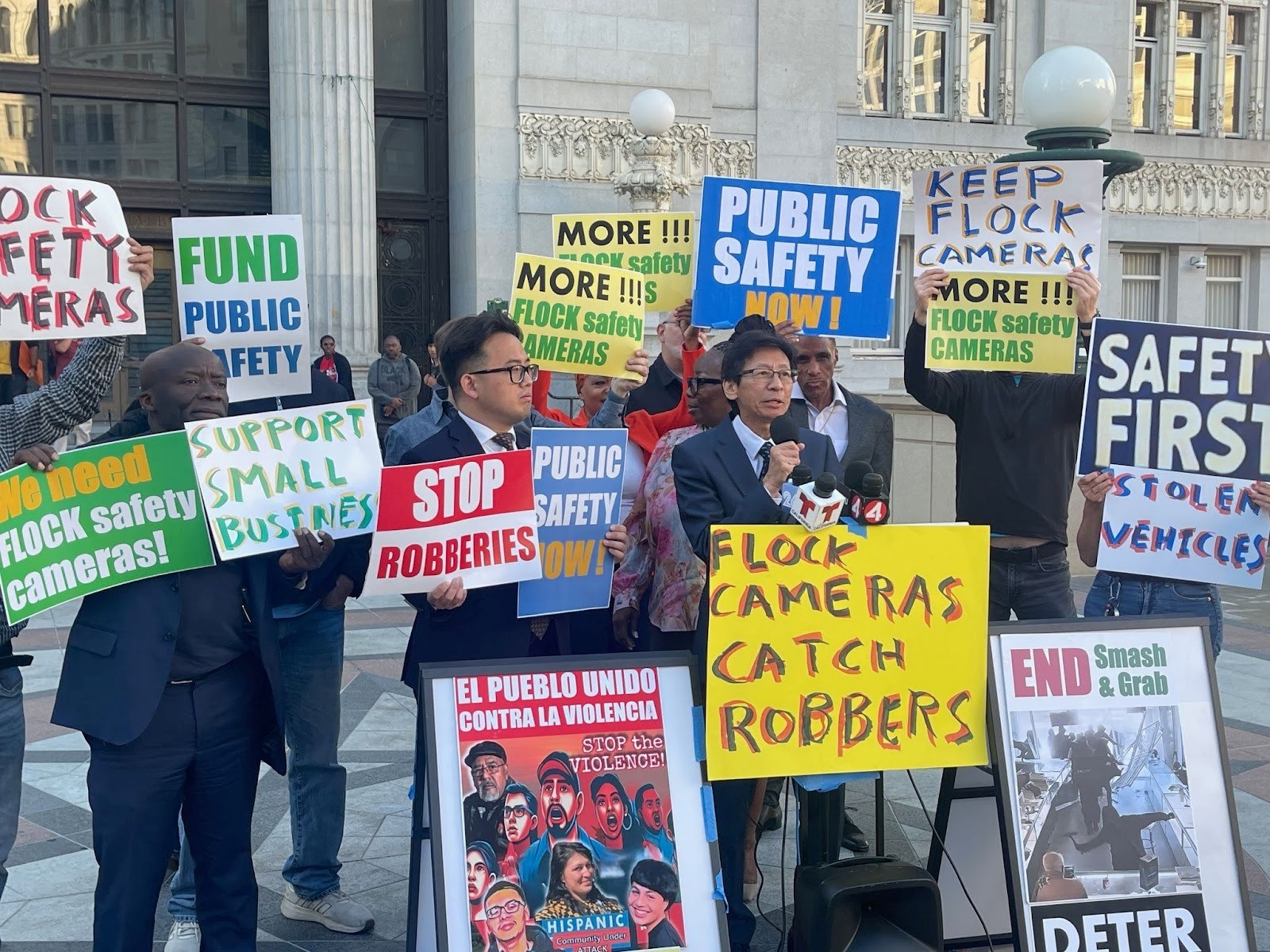

That’s why I urge the Oakland City Council to expand the city’s use of Flock ALPR technology with their vote at Tuesday’s Council meeting. They should do so with strong, enforceable safeguards around privacy, data retention, sharing, transparency, and independent oversight.

This is the real test of leadership in the tech age. Not whether we say yes to innovation or no to it, but whether we are capable of using powerful tools without becoming captive to them.

The trend line is moving in the right direction. The tools exist to keep it there.The only open question is whether we’ll use our power wisely — or let fear, inertia, or ideology slow the work of keeping people safe.

Flock cameras are a powerful tool to help keep the momentum going, yet they’re not a magic wand

Automatic License Plate Reader (ALPR) systems like Flock Safety sit right at the fault line between liberation through safety and oppression through surveillance.

A national study of 123 law enforcement agencies, conducted with oversight from criminology researchers at Texas Christian University and the University of Texas at Tyler, found that adding one Flock camera per sworn officer correlates with about a 9.1% increase in crime clearance rates, and that Flock data is now involved in solving about 10% of reported crimes nationwide (Police1+1).

And locally in Oakland, clearance rates in Oakland have risen about 11% since Flock cameras were installed in 2024, and now roughly one-third of homicide cases now involve Flock data (KTVU FOX 2 San Francisco). That’s not abstract; that’s grieving families getting answers they never would have had.

The State of California has already leaned in, partnering with Flock to deploy around 480 high-tech cameras in and around Oakland, including nearly 300 on city streets and the rest on state highways. Data from that project is supposed to be kept for 28 days and limited to use by California law enforcement (The Guardian). And according to OPD, Flock data in Oakland is owned by the city, deleted after 30 days unless tied to an active investigation, and not shared with ICE or out-of-state agencies (KTVU FOX 2 San Francisco).

Taken together, these are serious public-safety benefits in a city that still has one of the highest violent crime rates in America. Technology isn’t the whole answer. But refusing to use tools that are demonstrably helping clear shootings, robberies, and carjackings when strong safeguards are available to protect against abuse is its own kind of choice.

We need both: more capability to stop violence, and more protection against abuse.

The risks are real but we can mitigate them

Nationally, ALPR use has exploded. A Brennan Center review found tens of thousands of readers in use, with over 90% of big-city departments now use ALPRs (Brennan Center for Justice).

Most of those scans have nothing to do with crime. A memo from the University of Michigan’s Ford School cites data from Maryland showing that for every one million plates scanned, only about 47 had any potential connection to a serious crime (STPP). That means vast databases dominated by information about people who’ve done nothing wrong.

We have seen what happens when powerful tools lack guardrails:

A police lieutenant in one department was arrested after using ALPR data to stalk his ex-wife (STPP).

The NYPD was documented scanning cars parked outside mosques, effectively targeting Muslim communities for dragnet surveillance (STPP).

The Electronic Frontier Foundation found ALPR use in Oakland was concentrated disproportionately in Black and Latino neighborhoods (STPP).

The same systems that help us find a car used in a drive-by could also be used to track immigrants, political activists, or people seeking health care in another state. The power is neutral; the use is not.

Good technology can be corrupted. Good ideas can be co-opted. Good people can be tempted. That’s not a reason to abandon the tools; it’s a reason to govern them.

What does “using our powers for good” actually look like?

If we want to expand Flock in Oakland — and I believe we should — we have to pair that expansion with hard, enforceable safeguards, many of which are already recommended by independent policy experts (STPP+1).

Here’s what that should look like:

Tight Retention and Access Rules

Keep non-hit plate data for a very short period (e.g., 30 days or less), with anything longer tied only to a specific case number and legal process.

Require a warrant or documented probable cause for broad historical searches not tied to a current investigation.

Ironclad Data-Sharing Limits

Prohibit sharing with ICE or out-of-state agencies except where strictly required by law and disclosed publicly.

Bar any integration that would let outside agencies run bulk, nationwide queries through Oakland’s data without local oversight.

Full Transparency

Publish the ALPR use policy, camera placement criteria, and retention rules in plain language.

Provide regular public reports: how many plates scanned, how many hits, what types of cases they supported, and where the cameras are generally located.

Independent Oversight And Audits

Empower Oakland’s Community Policing Advisory Board (or another body with a broad community safety mandate) to approve policies, review audits, and recommend suspensions or terminations of the program.

Log every search and alert, then audit for misuse, bias, and compliance with sanctuary and privacy laws.

Equity And Effectiveness Metrics

Evaluate not just how many crimes are solved, but which crimes and in which neighborhoods.

Pair tech investments with funding for violence prevention, youth programs, re-entry support, and small-business stabilization in the same communities where cameras are deployed.

This is what it means to use power for good instead of evil in the real world: not trusting technology blindly, and not demonizing it reflexively, but binding it with rules that reflect our values.

So here’s my position, plainly:

Oakland needs every responsible tool it can get to keep people safe, especially in neighborhoods that have paid the highest price for both crime and over-policing.

Flock ALPR technology has already shown it can help solve serious crimes faster, including homicides, here and across the country (KTVU FOX 2 San Francisco+1).

The risks of misuse are real, particularly for immigrants, activists, and communities of color — and those risks can and must be minimized through strict policy, technical safeguards, and independent oversight (STPP+2Brennan Center for Justice+2).

If you agree with me, please email the Oakland City Council by completing the following form, urging them to expand the city’s use of Flock ALPR technology at Tuesday’s council meeting alongside robust, enforceable safeguards on data retention, data sharing, transparency, and oversight.

Technology will not save us. People will. And we must have the courage to shape these tools to serve justice, safety, and improved quality of life for all Oaklanders.

Comments